Music Music Music

Djembe History

The djembe (pronounced 'jem-beh') is the goblet-shaped hand drum from West Africa. Djembe history is a rich and diverse subject, but it can be difficult to verify. Africans have long passed...

Djembe History

The djembe (pronounced 'jem-beh') is the goblet-shaped hand drum from West Africa. Djembe history is a rich and diverse subject, but it can be difficult to verify. Africans have long passed...

Humidity, Temperature and Storage for Guitars (...

Wood is easily affected by temperature and humidity changes, therefore taking care of the surroundings of your guitar is very important in order to keep the instrument in a proper...

Humidity, Temperature and Storage for Guitars (...

Wood is easily affected by temperature and humidity changes, therefore taking care of the surroundings of your guitar is very important in order to keep the instrument in a proper...

Spanish Guitars - Jordi and Javier Camps - Now ...

Camps Guitars was founded in 1945 with the aim of making an instrument adapted to the specific needs of every musician. The founder Juan Camps decided to enroll in guitar manufacturing...

Spanish Guitars - Jordi and Javier Camps - Now ...

Camps Guitars was founded in 1945 with the aim of making an instrument adapted to the specific needs of every musician. The founder Juan Camps decided to enroll in guitar manufacturing...

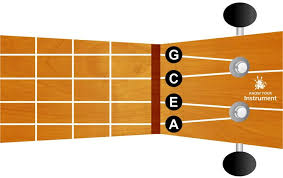

How Do I Tune My Ukulele?

How To Properly Tune Your Ukulele The open strings of the ukulele are as follows:• G: the 4th string (most to the left on the fretboard)• C: the 3rd string•...

How Do I Tune My Ukulele?

How To Properly Tune Your Ukulele The open strings of the ukulele are as follows:• G: the 4th string (most to the left on the fretboard)• C: the 3rd string•...

What types of Ukuleles Are There?

The Sizes So there are four main sizes in ukuleles. Soprano, concert, tenor and baritone. The soprano is the most common size and the smallest at 20" long. It is the...

What types of Ukuleles Are There?

The Sizes So there are four main sizes in ukuleles. Soprano, concert, tenor and baritone. The soprano is the most common size and the smallest at 20" long. It is the...

Can You Tune A Ukulele With A Guitar Tuner

First of all, you need to check if your Guitar Tuner is Chromatic, meaning it has all the notes, or does it have capacity for Ukulele? The problem is that...

Can You Tune A Ukulele With A Guitar Tuner

First of all, you need to check if your Guitar Tuner is Chromatic, meaning it has all the notes, or does it have capacity for Ukulele? The problem is that...